A new tool developed with funding from NASA’s Earth Science Division helps decision makers and others assess how sea level rise and other factors will affect the frequency of high tide flooding in U.S. coastal locations in the next 50 to 100 years.

High-tide flooding, also known as “sunny day” or nuisance flooding, is an increasingly frequent occurrence in coastal areas around the United States. The Flooding Days Projection Tool is an online dashboard that projects the number of high tide flooding days per year for 97 U.S. cities, based on National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) impact thresholds. These thresholds provide a safety gap between regular high tide water levels and conditions that result in flooding. Coastal communities are built a certain elevation above sea level with these natural fluctuations in mind.

The tool is based on projections of sea level rise and the height of the highest astronomical tides, which vary on a predictable 18.6-year cycle that’s determined by the Moon’s orbit around Earth. Over multiple decades, changes in the Moon’s orbit cause cyclical variations in the height of high and low tides in certain regions. These changes occur slowly.

Get NASA's Sea Level Change News: Subscribe to the Newsletter »

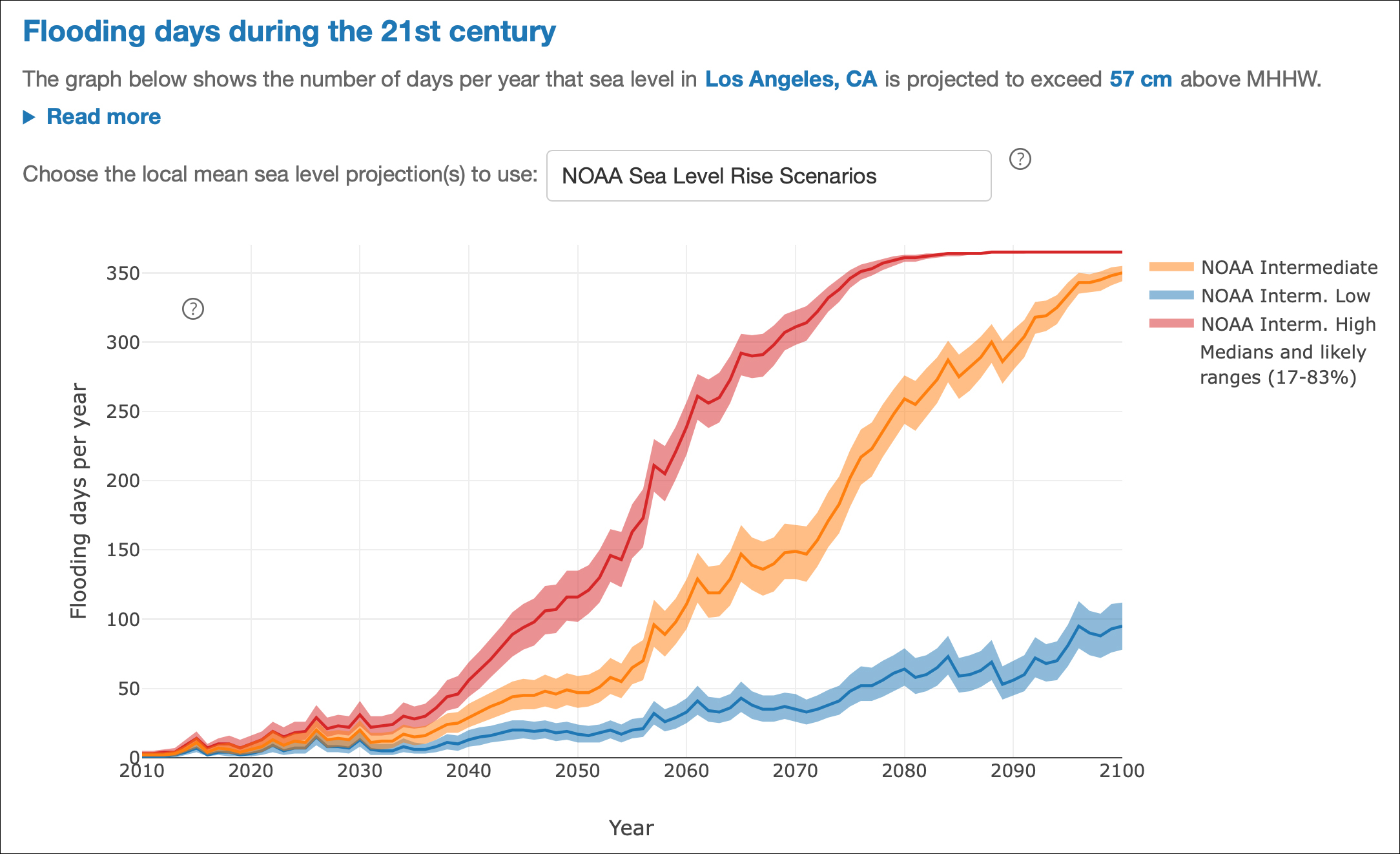

The inflection in the 2030s and subsequent rapid increase are related to the interaction between sea level rise and predictable cycles in the height of high tides that span multiple decades. Credit: University of Hawaii Sea Level Center

“Tides aren’t as constant as people think they are,” said Phil Thompson, director of the University of Hawaii’s Sea Level Center in Honolulu and an assistant professor in the university’s Department of Oceanography, who developed the tool. “They change on long time scales.”

When high tides get lower, the net effect of sea level rise on flooding is reduced. The tool predicts this will happen in many U.S. locations from the mid-2020s until the mid-2030s, when high tides will once again get higher. When increases in high tides synch up with increases in global or regional sea level rise and other factors that cause sea levels to vary, there’s a potential for rapid increases in coastal water levels and associated impacts. For regions where the rate of sea level rise is already accelerating, such as along the U.S. West Coast, the cycle will exacerbate those impacts.

“We’ll observe a rapid increase in high tide flooding days for regions around the globe,” Thompson said. “For a place like California, the height of high tides will increase 3 to 5 centimeters over 10 years, on top of a similar increase from sea level rise that’s driven by climate change.”

Thompson says this will result in numerous changes. For example, assuming NOAA’s intermediate sea level rise scenario, beginning in the mid-2030s, the frequency of high tide flooding events each year in the Los Angeles coastal area will go from fewer than 10 to more like 40. In San Diego, annual flooding events will increase from 15 to more than 60. And in San Francisco, they’ll go from fewer than 10 to almost 40 per year.

“The last time this lunar cycle increased high tides, we couldn’t see the impacts because sea level rise hadn’t pushed these events over the flooding threshold yet,” said Thompson. “But next time we will, because sea level rise is ongoing.”