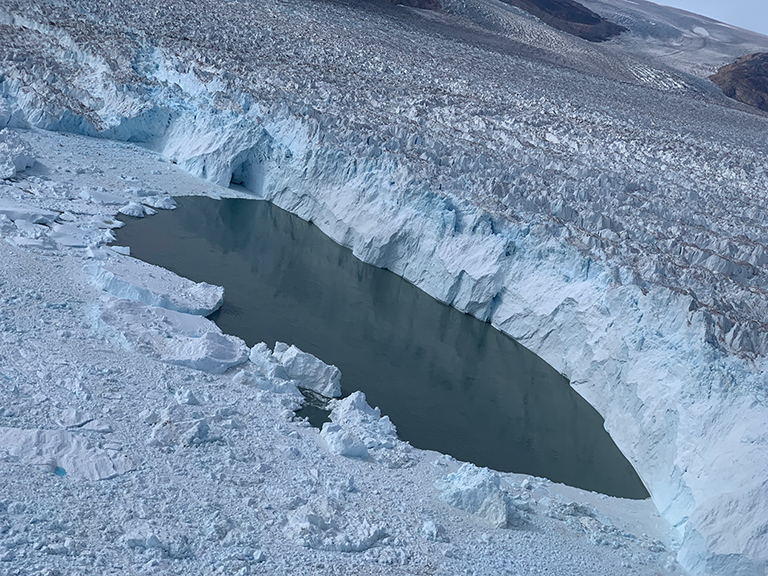

In March, a NASA-led research team announced that Jakobshavn Isbrae, Greenland's fastest-flowing and thinning glacier over the past two decades, is now flowing more slowly, thickening and advancing toward the ocean instead of retreating farther inland.

On the surface, that sounds like great news. After all, if this glacial behemoth, which drains seven percent of Greenland, is slowing, certainly that must mean that global warming is also slowing, right?

Wrong. The findings have been interpreted that way by some, suggesting that the study results were evidence that global warming is slowing or stopping. However, the facts paint a different picture, as a quick review of the study’s key findings illustrates. To recap:

- The recent changes in Jakobshavn, located on Greenland’s west coast, are attributed to the 2016 cooling of an ocean current that carries water to the glacier’s ocean face, likely due to a shift in the North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO) that took place in 2015. The NAO is an oceanic climate pattern that causes northern Atlantic water temperatures to alternate between warm and cold every five to 20 years. The glacier’s dramatic slowdown coincided with the arrival of the cooler waters near Jakobshavn that summer.

- Water temperatures near the glacier are now colder than they’ve been since the mid-1980s. The colder water isn’t melting the ice at the front of and beneath the glacier as quickly as the warmer water did.

- Jakobshavn’s changes are temporary. When the NAO flips again, the glacier will most likely resume accelerating and thinning, as warm waters return to continue melting it from beneath.

Following the study’s publication, additional analyses show Jakobshavn grew thicker by 22 and 33 yards (20 to 30 meters) each year from 2016 to 2019.

How ocean temperatures impact Greenland’s glaciers

Many factors can speed up or slow down a glacier’s rate of ice loss. These include the shape of the bedrock under it and along its sides, short-term variations in ocean temperature and circulation, air temperature and precipitation and climate change. To better understand the role ocean temperatures play, four years ago NASA launched the Oceans Melting Greenland (OMG) campaign to measure ocean temperature and salinity around Greenland.

While Greenland is an island, it’s surrounded by a continental shelf beneath the ocean surface. The shelf forms a natural barrier that keeps the deeper, warmer waters of the Atlantic from reaching parts of the Greenland coast. Near the coast, the average ocean depth is about 1,300 to 1,600 feet (400 to 500 meters), whereas in the deep ocean, 30 to 200 miles (50 to 320 kilometers) offshore, waters usually reach depths of around 13,100 feet (4,000 meters).

However, deep underwater canyons cut through the continental shelf, allowing the faces of many Greenland glaciers to sit in warm, deep water. A key OMG objective has been to conduct the most comprehensive mapping to date of the sea floor around Greenland to see where these canyons are located. As a result, we now know just how many glaciers sit in deep water, how deep the water is, and how fjords around Greenland connect to warm offshore waters.

“We’ve filled in huge gaps in our knowledge of the sea floor depth around Greenland,” said OMG Principal Investigator and study co-author Josh Willis of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California. “Some of the glaciers sit in about 3,300 feet (1,000 meters) of water, the equivalent of 10 football fields below the surface. In fact, everything we’ve found suggests Greenland’s glaciers are more threatened than we expected.”

"Everything we’ve found suggests Greenland’s glaciers are more threatened than we expected."

Parsing out the facts about Jakobshavn

While Jakobshavn’s behavior may be confusing to some, there is no evidence that its growth is indicative of any slowdown in global warming. Global carbon dioxide concentrations aren’t dropping, global atmospheric and ocean temperatures aren’t dropping and global sea levels aren’t falling. In fact, all evidence points strongly in the opposite direction.

What the current events at Jakobshavn do show us is that, in addition to the longer-term changes happening to Earth due to human-produced emissions of greenhouse gases, natural processes, such as ocean oscillations, also play key roles in the shorter-term changes we’re observing on our planet.

“The NAO is a cycle that’s been going back and forth for centuries,” said Willis. “There’s no evidence that it or other climate cycles like the Pacific Decadal Oscillation or El Niño are going to stop. The last time the NAO switched to a warm phase was in the mid- to early-90s. So we expect it to switch again, sometime between now and the next 15 years. That’s one of the reasons why studies like OMG are so important. At the end of the day, Greenland is still losing ice, other Greenland glaciers are still retreating and the oceans are warming.”

The bottom line for Jakobshavn is that it is still a major contributor to sea level rise and it continues to lose more ice mass than it’s gaining.

What’s ahead for OMG?

In early August, the OMG team arrived in Greenland to begin its fourth year of ocean surveys to see how the water is changing. The start of this year’s survey came on the heels of a record melting event in late July and early August. The team again dropped sensors in front of Jakobshavn to see if the water is still cold and whether we can expect another year of growth, or for it to resume retreating. The investigation also examined whether the NAO shift is impacting other glaciers.

Within the next year and a half, the OMG team will complete its comprehensive categorization of all of Greenland’s 200-plus glaciers to quantify the role the ocean is playing in their retreat and how much ice the island is losing because of it. Willis says the team also plans to look at data from the NASA/German Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment (GRACE) Follow-On mission to see whether the NAO’s impact is big enough to affect the ice sheet’s overall mass balance.

“If we’re lucky, OMG may also catch the reversal of the cooling signal now impacting Jakobshavn,” he said. “That will tell us what happens when the glaciers start to retreat again as warm water comes back, and just how sensitive the whole thing is to the water. Understanding these natural fluctuations will help us calibrate how Greenland’s ice is going to behave in the long run.”