News | April 21, 2016

New maps chart Greenland glaciers' melting risk

A UC Irvine team measures the seafloor off the coast of Greenland. Image credit: UCI/Maria Stenzel

Many large glaciers in Greenland are at greater risk of melting from below than previously thought, according to new maps of the seafloor around Greenland created by an international research team. Like other recent research findings, the maps highlight the critical importance of studying the seascape under Greenland's coastal waters to better understand and predict global sea level rise.

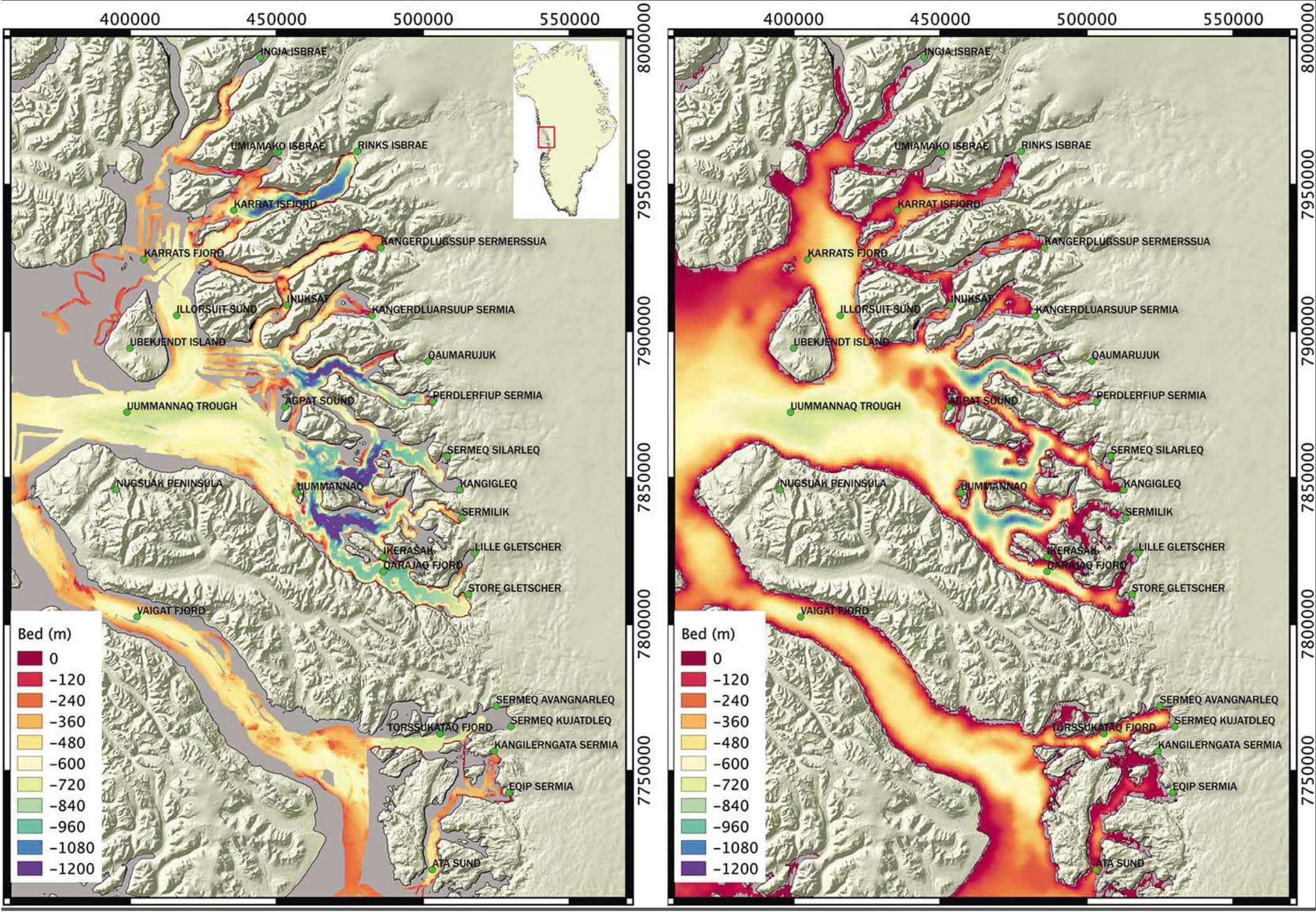

Researchers from the University of California, Irvine; NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, California; and other research institutions combined all observations their various groups had made during shipboard surveys of the seafloors in the Uummannaq and Vaigat fjords in west Greenland between 2007 and 2014 with related data from NASA's Operation Icebridge and the NASA/U.S. Geological Survey Landsat satellites. They used the combined data to generate comprehensive maps of the ocean floor around 14 Greenland glaciers. Their findings show that previous estimates of ocean depth in this area were as much as several thousand feet too shallow.

Why does this matter? Because glaciers that flow into the ocean melt not only from above, as they are warmed by sun and air, but from below, as they are warmed by water.

In most of the world, a deeper seafloor would not make much difference in the rate of melting, because typically ocean water is warmer near the surface and colder below. But Greenland is exactly the opposite. Surface water down to a depth of almost a thousand feet (300 meters) comes mostly from Arctic river runoff. This thick layer of frigid, fresher water is only 33 to 34 degrees Fahrenheit (1 degree Celsius). Below it is a saltier layer of warmer ocean water. This layer is currently more than more than 5 degrees F (3 degrees C) warmer than the surface layer, and climate models predict its temperature could increase another 3.6 degrees F (2 degrees C) by the end of this century.

About 90 percent of Greenland's glaciers flow into the ocean, including the newly mapped ones. In generating estimates of how fast these glaciers are likely to melt, researchers have relied on older maps of seafloor depth that show the glaciers flowing into shallow, cold seas. The new study shows that the older maps were wrong.

"While we expected to find deeper fjords than previous maps showed, the differences are huge," said Eric Rignot of UCI and JPL, lead author of a paper on the research. "They are measured in hundreds of meters, even one kilometer [3,300 feet] in one place." The difference means that the glaciers actually reach deeper, warmer waters, making them more vulnerable to faster melting as the oceans warm.

Coauthor Ian Fenty of JPL noted that earlier maps were based on sparse measurements mostly collected several miles offshore. Mapmakers assumed that the ocean floor sloped upward as it got nearer the coast. That's a reasonable supposition, but it's proving to be incorrect around Greenland.

Rignot and Fenty are co-investigators in NASA's five-year Oceans Melting Greenland (OMG) field campaign, which is creating similar charts of the seafloor for the entire Greenland coastline. Fenty said that OMG's first mapping cruise last summer found similar results. "Almost every glacier that we visited was in waters that were far, far deeper than the maps showed."

The researchers also found that besides being deeper overall, the seafloor depth is highly variable. For example, the new map revealed one pair of side-by-side glaciers whose bottom depths vary by about 1,500 feet (500 meters). "These data help us better interpret why some glaciers have reacted to ocean warming while others have not," Rignot said.

The lack of detailed maps has hampered climate modelers like Fenty who are attempting to predict the melting of the glaciers and their contribution to global sea level rise. "The first time I looked at this area and saw how few data were available, I just threw my hands up," Fenty said. "If you don't know the seafloor depth, you can't do a meaningful simulation of the ocean circulation."

The maps are published in a paper titled "Bathymetry data reveal glaciers vulnerable to ice-ocean interaction in Uummannaq and Vaigat glacial fjords, west Greenland," in the journal Geophysical Research Letters. The other collaborating institutions are Durham University and the University of Cambridge, both in the U.K.; GEOMAR Helmholtz Center for Ocean Research, Kiel, Germany; and the University of Texas at Austin.

For more information on OMG, visit:

https://omg.jpl.nasa.gov/portal/

NASA uses the vantage point of space to increase our understanding of our home planet, improve lives and safeguard our future. NASA develops new ways to observe and study Earth's interconnected natural systems with long-term data records. The agency freely shares this unique knowledge and works with institutions around the world to gain new insights into how our planet is changing.

For more information about NASA's Earth science activities, visit: